You can also have custom metadata: I'll often use that to track things which get in a horrible muddle so easily, such as the date or time of the scene, or the ages of the main character. The standard meta-data includes what's on the famous "index cards": a name for the document, and a synopsis of what it contains, and as much or as little as you like of colour-coding (for, say, the setting of each scene, or the point-of-view) and stamping (marking, say, whether a document is a rough-cut or a final draft). Second, each document has a set of associated meta-data, which it always carries with it, but you don't have to see if you don't want to. You can work on a whole chapter, say, while also being able to handle or move the individual scenes separately if you want to. The big difference is that Scrivener will display your documents seamlessly, in "Scrivenings" mode, one after another so you can read them as a single document with the join between marked or not, as you choose. A document could be one word, one "beat", one scene, one chapter, or a whole novel. I haven't used everything it does, but this is how it's looking to me so far.įirst, the essence of Scrivener is that the basic unit is a "document", which is just like any word-processing document. So I'm going explain how it works as a way of explaining why I think it's worth sticking at, and some ways of getting to know it. But, like any powerful, flexible program, it gets a bit of getting used to.

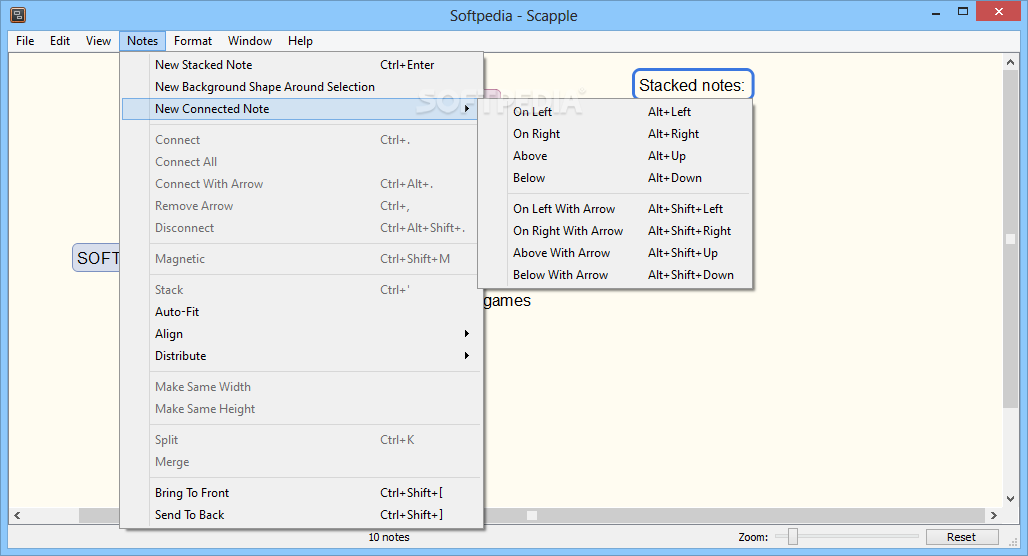

#SCAPPLE INSERT PICTURE WINDOWS#

It's available for Windows and Mac, with iOS available too, and a Linux version in the works. It's the only such program which I know is used by slews of other professionals for writing fiction, creative non-fiction and the more factual and technical kind of non-fiction, and I see exactly why. It was born apparently from the different but not unrelated challenges of writing a PhD and a novel, and inspired by Hilary Mantel's description of how she works, and that pedigree shows. A word processor is essential next, but the many "novel-writing" programs on the market seemed to be little more than toys dreamed up by non-writing geeks, to sell or give away to beginners writers desperate for ways to make the weird business of creating something out of nothing more manageable.īut Scrivener is different, and though I'm neither a techno-phobe nor a geek, I'm now a complete convert.

Oh, and piles and piles of scrap paper for all the notes and ideas and snaglists. All I actually need to write a novel is a stack of identical A4 notebooks (makes keeping the wordcount easier), a good biro (fat enough not to get RSI), and a plotting grid.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)